The senses of smell (olfaction) and taste (gustation) operate in a kind of synergistic, deeply personal alchemy, guiding our nutritional choices, signaling danger from smoke or spoiled food, and enriching the fabric of daily experience. Yet, for a surprising number of people, this fundamental sensory pair can be partially or completely disrupted, leading to the conditions of anosmia (loss of smell) or ageusia (loss of taste), or their reduced counterparts, hyposmia and hypogeusia. It’s an issue that, while rarely life-threatening on its own, severely impacts one’s quality of life and, crucially, can serve as a diagnostic canary in the coal mine for a range of underlying health problems. The question of what causes this loss is a labyrinth of anatomical pathways, from the delicate cilia in the nose to the cranial nerves that relay signals to the brain, and the diverse causes can be broadly categorized into three main arenas: those that physically block the path of odors, those that directly damage the sensory nerves or tissues, and those that originate in the central nervous system.

The Diverse Causes Can Be Broadly Categorized into Three Main Arenas

The diverse causes can be broadly categorized into three main arenas: those that physically block the path of odors, those that directly damage the sensory nerves or tissues, and those that originate in the central nervous system.

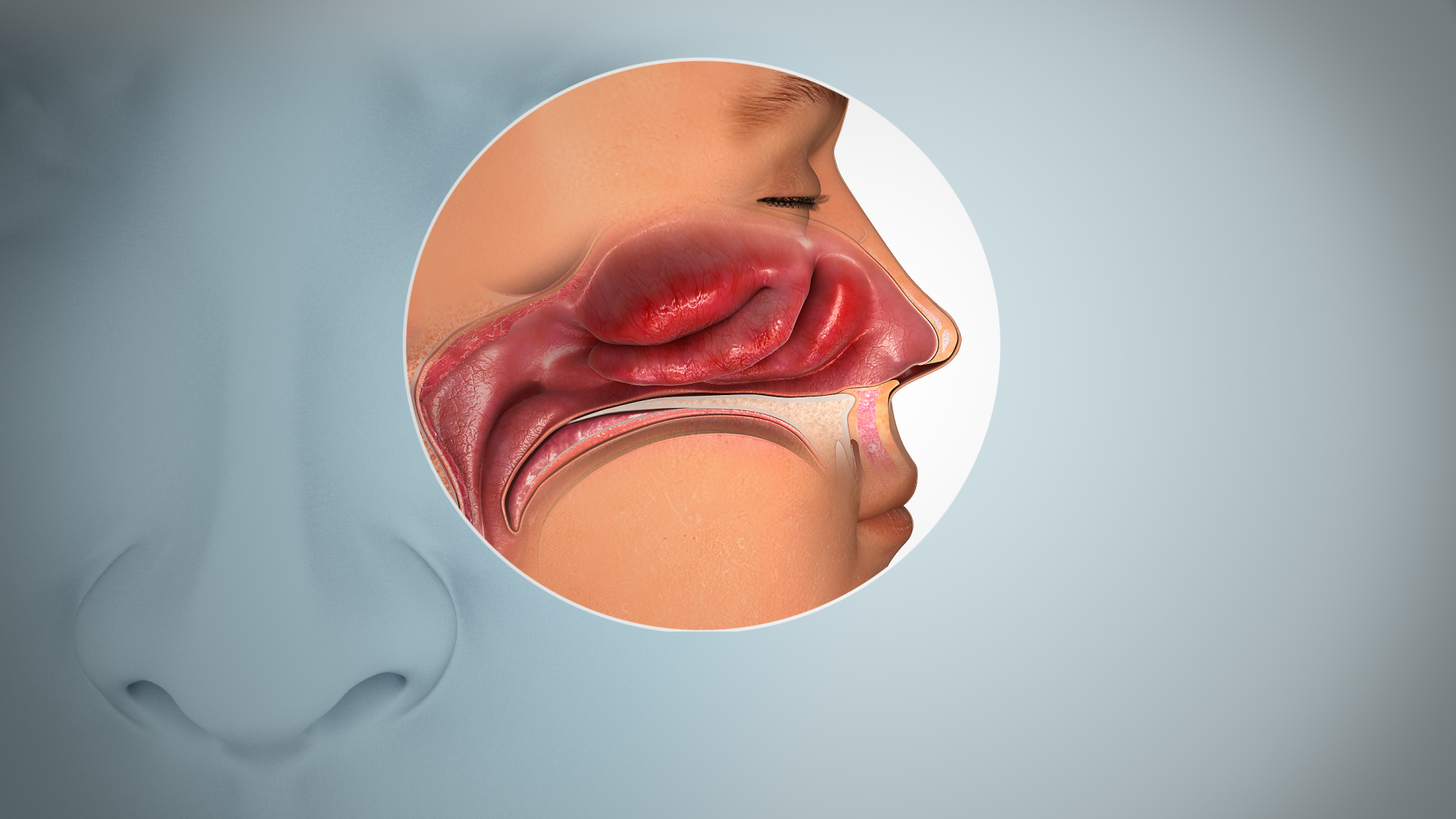

At the most straightforward level, the impairment of smell and taste is often conductive, meaning that the chemical stimuli—odor molecules for smell, tastants for taste—are simply prevented from reaching their receptor sites. This is the common, temporary loss experienced during a severe cold or sinus infection, where mucosal swelling and thick mucus physically obstruct the air from reaching the olfactory neuroepithelium high in the nasal cavity. The epithelial inflammation caused by allergic rhinitis or a non-allergic but persistent inflammatory condition can create a similar barrier. More enduring physical obstructions include nasal polyps, which are non-cancerous growths, or the rare but more serious nasal or paranasal sinus tumors. In all these instances, the underlying sensory apparatus remains intact; the loss is a mechanical failure, and treating the congestion or removing the physical barrier, often through surgical intervention in the case of polyps, frequently restores function. However, assuming that all sinonasal symptoms are merely mechanical is a dangerous oversimplification, especially when the loss of function persists long after the acute infection or inflammation seems to have subsided.

The Olfactory Neuroepithelium is Destroyed

Prior upper respiratory infection (URI), especially influenza, is implicated in 14 to 26% of all patients that present with hyposmia or anosmia.

A more concerning and often more permanent category of loss stems from sensorineural damage, where the delicate cells responsible for translating chemical signals into neural impulses are injured or destroyed. The most common culprit here, outside of severe head trauma, is a viral infection. Prior upper respiratory infection (URI), especially influenza, is implicated in 14 to 26% of all patients that present with hyposmia or anosmia. Crucially, the viral impact isn’t just about temporary blockage; certain neurotropic viruses, including but not limited to SARS-CoV-2, can cause direct or indirect inflammatory damage to the olfactory sensory neurons themselves, or to the vital supporting cells within the nasal epithelium. This damage can range from a minor, temporary disruption of the cell turnover process to significant, permanent destruction of the receptor cells. For taste, direct damage to the taste buds or the intricate neural network of the tongue and mouth, perhaps from severe oral infections, radiation therapy for head and neck cancers, or thermal burns, leads to ageusia. The regenerative capacity of these cells is limited, and the recovery period can be long and uncertain, sometimes never fully returning to the pre-injury level.

Head Trauma and Neurologic Symptoms or Signs

The nerve pathways are exceptionally vulnerable to sudden, forceful movement, particularly where the delicate olfactory nerve filaments pass through the cribriform plate of the skull base.

Beyond infection, head trauma is a primary cause of sudden, permanent anosmia. The nerve pathways are exceptionally vulnerable to sudden, forceful movement, particularly where the delicate olfactory nerve filaments pass through the cribriform plate of the skull base. A sharp, non-penetrating blow, even one that does not cause a loss of consciousness, can shear these fine nerve bundles, disconnecting the sensory receptors in the nose from the olfactory bulb—the brain’s processing center for smell. The resultant loss is abrupt and often profound. Furthermore, any condition causing structural or inflammatory damage higher up in the central nervous system can compromise chemosensory function. Neurological symptoms or signs, such as sudden, unexplained anosmia alongside other deficits, must raise immediate red flags for conditions like brain tumors, aneurysms, or even the subtle onset of a stroke, especially when the loss is unilateral. These central causes require urgent imaging and neurological assessment to rule out immediately treatable, life-threatening pathologies that are far removed from a simple blocked nose.

The Two Most Prominent Neurodegenerative Disorders

Olfactory dysfunction is linked to the two most prominent neurodegenerative disorders, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

The role of chemosensory loss as an early biomarker for systemic or neurodegenerative disease is one of the most compelling and often underappreciated aspects of the issue. Olfactory dysfunction is linked to the two most prominent neurodegenerative disorders, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. In many patients who later develop these conditions, a subtle but measurable hyposmia can precede the motor or cognitive symptoms by years. This suggests that the pathological changes in the brain begin in the olfactory structures, offering a potential window for earlier diagnosis and, eventually, pre-symptomatic therapeutic intervention. Other systemic diseases like diabetes, which can damage small nerve fibers (neuropathy), and conditions like multiple sclerosis or Sjögren’s syndrome, which involve systemic inflammation or nerve destruction, can also contribute to taste or smell impairment, demonstrating that the loss of these senses is not merely a localized ENT problem but often a mirror reflecting the body’s overall systemic health.

Medications and Illicit Drugs

Hundreds of medications have loss of taste as a potential side effect, including antibiotics, antivirals, and certain heart and neurologic drugs.

An often-overlooked factor in acquired chemosensory loss is pharmacological intervention. Hundreds of medications have loss of taste as a potential side effect, including antibiotics, antivirals, and certain heart and neurologic drugs. The mechanisms are varied: some drugs, like certain ACE inhibitors used for high blood pressure, can directly interfere with the taste receptor function; others may cause xerostomia (dry mouth), a condition that is itself a major contributor to taste dysfunction because saliva is necessary to dissolve tastants and deliver them to the taste buds. The consumption of illicit drugs, particularly those inhaled nasally, can cause direct caustic or inflammatory damage to the nasal mucosa and the underlying olfactory cells, leading to a permanent sensorineural loss. For patients experiencing taste or smell loss while on a complex medication regimen, a thorough review of their drug list is essential, and sometimes, simply adjusting the dosage or switching to an alternative drug can restore function, though this must always be done under strict medical supervision.

Nutritional Deficiencies and Endocrine Imbalances

The subtle, yet crucial, roles of various micronutrients in maintaining chemosensory health mean that nutritional deficiencies can manifest as a diminished sense of taste or smell.

The subtle, yet crucial, roles of various micronutrients in maintaining chemosensory health mean that nutritional deficiencies can manifest as a diminished sense of taste or smell. A common example is zinc deficiency, a micronutrient vital for cell division and the function of many enzymes, including those in the taste buds and olfactory epithelium. Insufficient levels can impede the normal, necessary turnover and regeneration of these sensory cells, leading to a noticeable drop in sensory acuity. Similarly, deficiencies in certain B vitamins, particularly B12, can contribute to nerve damage (neuropathy) that affects the cranial nerves involved in taste. Furthermore, hormonal and endocrine imbalances, such as an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism), have been linked to chemosensory dysfunction, although the exact mechanism is often indirect, possibly related to generalized metabolic slowing or mucosal changes. A comprehensive diagnostic workup for unexplained or chronic loss should therefore always include an assessment of key vitamin and mineral levels, as well as an evaluation of basic endocrine function.

Progressive Confusion and Recent Memory Loss

Slowly progressive anosmia in an older patient with no other symptoms or findings suggests normal aging as the cause.

While the dramatic causes—viruses, trauma, tumors—receive the most attention, the most pervasive cause of gradual olfactory decline is simply aging. Slowly progressive anosmia in an older patient with no other symptoms or findings suggests normal aging as the cause. Olfactory function peaks in early adulthood and begins a slow, often unnoticed decline around the age of 60, accelerating thereafter. This is thought to be a result of the cumulative wear and tear on the delicate olfactory epithelium, a decrease in the number of functional sensory neurons, and subtle changes in the central processing centers of the brain. However, a clinician must be exceptionally cautious not to prematurely attribute loss to ‘just age,’ especially when it is coupled with other signs. For instance, progressive confusion and recent memory loss in an older patient strongly suggest a more sinister, active process like Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia, where the loss of smell is a known, and highly relevant, early symptom. The differentiation between benign age-related decline and a neurodegenerative process is one of the most sensitive and important diagnostic responsibilities in this field.

The Inability to Capture Uniqueness

The overall trajectory of research and clinical practice in this area emphasizes that loss of olfactory function is a critical, complex signal, not merely an inconvenience.

Ultimately, understanding what causes the loss of smell or taste demands an integrative, non-linear approach that avoids the reductionist impulse to assign a single cause. It requires an appreciation for the vulnerability of the peripheral structures (like the olfactory neuroepithelium), the potential for systemic interference (drugs, hormones, nutrition), and the critical role of the central nervous system (neurodegeneration, tumors). The diagnostic path often twists and doubles back, moving from the common cold to brain imaging, from zinc levels to a neurological exam. The overall trajectory of research and clinical practice in this area emphasizes that loss of olfactory function is a critical, complex signal, not merely an inconvenience. It impacts emotional well-being, the enjoyment of food, and, critically, personal safety, demanding a thoughtful, human-centric investigation that acknowledges the profound, often disruptive, personal impact of this sensory deprivation.

A Critical, Complex Signal, Not Merely an Inconvenience

The mastery of this field is less about memorizing static guidelines and more about skillfully interpreting the subtle, fluctuating interplay between the growing fetus and the mother’s dynamic blood system.

The clinical presentation of chemosensory loss often forces the physician to become a detective, piecing together a history of seemingly unrelated events—a past viral illness, a new medication, a minor head bump—to construct a coherent pathological narrative. This narrative, which often involves multiple concurrent contributing factors, is fundamentally why the issue resists easy categorization and simple treatment protocols. The complexity underscores the fact that the senses of smell and taste are inextricably woven into a much larger physiological and neurological tapestry. The recovery, even when possible, may require olfactory training, targeted nutritional intervention, or the slow, uncertain regeneration of nerve tissue. Therefore, the immediate goal is always diagnosis, but the long-term objective must be to treat the patient with the full weight of their sensory deficit in mind, acknowledging that this loss is a profound barrier to a full and engaged life.

The Profound Barrier to a Full and Engaged Life

The differentiation between benign age-related decline and a neurodegenerative process is one of the most sensitive and important diagnostic responsibilities in this field.

The differentiation between benign age-related decline and a neurodegenerative process is one of the most sensitive and important diagnostic responsibilities in this field. Losing the ability to perceive the world’s chemical language is not trivial; it profoundly influences appetite, memory, and mood. The investigation must always be comprehensive, moving systematically from the peripheral airway to the central brain structures. The sheer number of potential etiologies—from polyps to Parkinson’s—demands a multi-disciplinary approach that rarely yields to a single, simple answer. It is a neurological and inflammatory puzzle that, when solved, offers not only a chance for sensory recovery but often provides crucial, early insight into the patient’s overall health and long-term prognosis.